BBC News, Islamabad

BBC

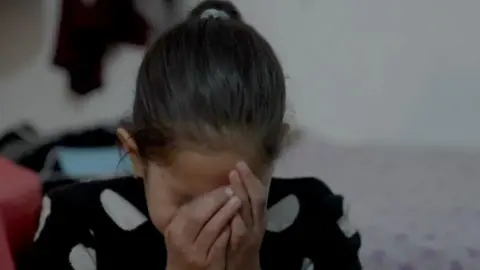

BBC“I’m scared,” sobs Nabila.

The 10-year-old’s life is limited to her one-bedroom home in Islamabad and the dirt road outside it. Since December she hasn’t been to her local school, when it decided it would no longer accept Afghans without a valid Pakistani birth certificate. But even if she could go to classes, Nabila says she wouldn’t.

“I was off sick one day, and I heard police came looking for Afghan children,” she cries, as she tells us her friend’s family were sent back to Afghanistan.

Nabila’s not her real name – all the names of Afghans quoted in this article have been changed for their safety.

Pakistan’s capital and the neighbouring city of Rawalpindi are witnessing a surge in deportations, arrests and detentions of Afghans, the UN says. It estimates that more than half of the three million Afghans in the country are undocumented.

Afghans describe a life of constant fear and near daily police raids on their homes.

Some told the BBC they feared being killed if they went back to Afghanistan. These include families on a US resettlement programme, that has been suspended by the Trump administration.

Pakistan is frustrated at how long relocation programmes are taking, says Philippa Candler, the UN Refugee Agency’s representative in Islamabad. The UN’s International Organization for Migration (IOM) says 930 people were sent back to Afghanistan in the first half of February, double the figure two weeks earlier. At least 20% of those deported from Islamabad and Rawalpindi had documentation from the UN Refugee Agency, meaning they were recognised as people in need of international protection.

But Pakistan is not a party to the Refugee Convention and has previously said it does not recognise Afghans living in the country as refugees. The government has said its policies are aimed at all illegal foreign nationals and a deadline for them to leave is looming. That date has fluctuated but is now set to 31 March for those without valid visas, and 30 June for those with resettlement letters.

Many Afghans are terrified amid the confusion. They also say the visa process can be difficult to navigate. Nabila’s family believes they have only one option: to hide. Her father Hamid served in the Afghan military, before the Taliban takeover in 2021. He broke down in tears describing his sleepless nights.

“I have served my country and now I’m useless. That job has doomed me,” he said.

His family are without visas, and are not on a resettlement list. They tell us their phone calls to the UN’s refugee agency go unanswered.

The BBC has reached out to the agency for comment.

The Taliban government has previously told the BBC all Afghans should return because they could “live in the country without any fear”. It claims these refugees are “economic migrants”.

But a UN report in 2023 cast doubt on assurances from the Taliban government. It found hundreds of former government officials and armed forces members were allegedly killed despite a general amnesty.

The Taliban government’s guarantees are of little reassurance to Nabila’s family so they choose to run when authorities are nearby. Neighbours offer each other shelter, as they all try to avoid retuning to Afghanistan.

The UN counted 1,245 Afghans being arrested or detained in January across Pakistan, more than double the same period last year.

Nabila says Afghans shouldn’t be forced out. “Don’t kick Afghans out of their homes – we’re not here by choice, we are forced to be here.”

There is a feeling of sadness and loneliness in their home. “I had a friend who was here and then was deported to Afghanistan,” Nabila’s mother Maryam says.

“She was like a sister, a mother. The day we were separated was a difficult day.”

I ask Nabila what she wants to do when she’s older. “Modelling,” she says, giving me a serious look. Everyone in the room smiles. The tension thaws.

Her mother whispers to her there are plenty of other things she could be, an engineer or a lawyer. Nabila’s dream of modelling is one she could never pursue under the Taliban government. With their restrictions on girls’ education, her mother’s suggestions would also prove impossible.

A new phase

Pakistan has a long record of taking in Afghan refugees. But cross-border attacks have surged and stoked tension between the two neighbours. Pakistan blames them on militants based in Afghanistan, which the Taliban government denies. Since September 2023, the year Pakistan launched its “Illegal Foreigners’ Repatriation Plan,” 836,238 individuals have now been returned to Afghanistan.

Amidst this current phase of deportations, some Afghans are being held in the Haji camp in Islamabad. Ahmad was in the final stages of the United States’ resettlement programme. He tells us when President Donald Trump suspended it for review, he extinguished Ahmad’s “last hope”. The BBC has seen what appears to be his employment letter by a Western, Christian non-profit group in Afghanistan.

A few weeks ago, when he was out shopping, he received a call. His three-year-old daughter was on the line. “My baby called, come baba police is here, police come to our door,” he says. His wife’s visa extension was still pending, and she was busy pleading with the police.

Ahmad ran home. “I couldn’t leave them behind.” He says he sat in a van and waited hours as police continued their raids. The wives and children of his neighbours continued trickling into the vehicle. Ahmad began receiving calls from their husbands, begging him to take care of them. They had already escaped into the woods.

His family was held for three days in “unimaginable conditions”, says Ahmad, who claims they were only given one blanket per family, and one piece of bread per day, and that their phones were confiscated. The Pakistani government says it ensures “no one is mistreated or harassed during the repatriation process”.

We attempt to visit inside Haji camp to verify Ahmad’s account but are denied entry by authorities. The BBC approached the Pakistani government and the police for an interview or statement, but no one was made available.

Scared of being detained or deported, some families have chosen to leave Islamabad and Rawalpindi. Others tell us they simply can’t afford to.

One woman claims she was in the final stages of the US resettlement scheme and decided to move with her two daughters to Attock, 80km (50 miles) west of Islamabad. “I can barely afford bread,” she says.

The BBC has seen a document confirming she had an interview with the IOM in early January. She claims her family is still witnessing almost daily raids in her neighbourhood.

A spokesman for the US embassy in Islamabad has said it is in “close communication” with Pakistan’s government “on the status of Afghan nationals in the US resettlement pathways”.

Outside Haji camp’s gates, a woman is waiting. She tells us she has a valid visa but her sister’s has expired. Her sister is now being held inside the camp, along with her children. The officers would not let her visit her family, and she is terrified they will be deported. She begins weeping, “If my country was safe, why would I come here to Pakistan? And even here we cannot live peacefully.”

She points to her own daughter who is sitting in their car. She was a singer in Afghanistan, where a law states women cannot be heard speaking outside their home, let alone singing. I turn to her daughter and ask if she still sings. She stares. “No.”

Article by:Source: