Serbia’s powerful populist leader Aleksandar Vučić was facing his biggest challenge yet as student-led demonstrations intensified at the weekend in what was being called the Balkan country’s greatest protest movement ever.

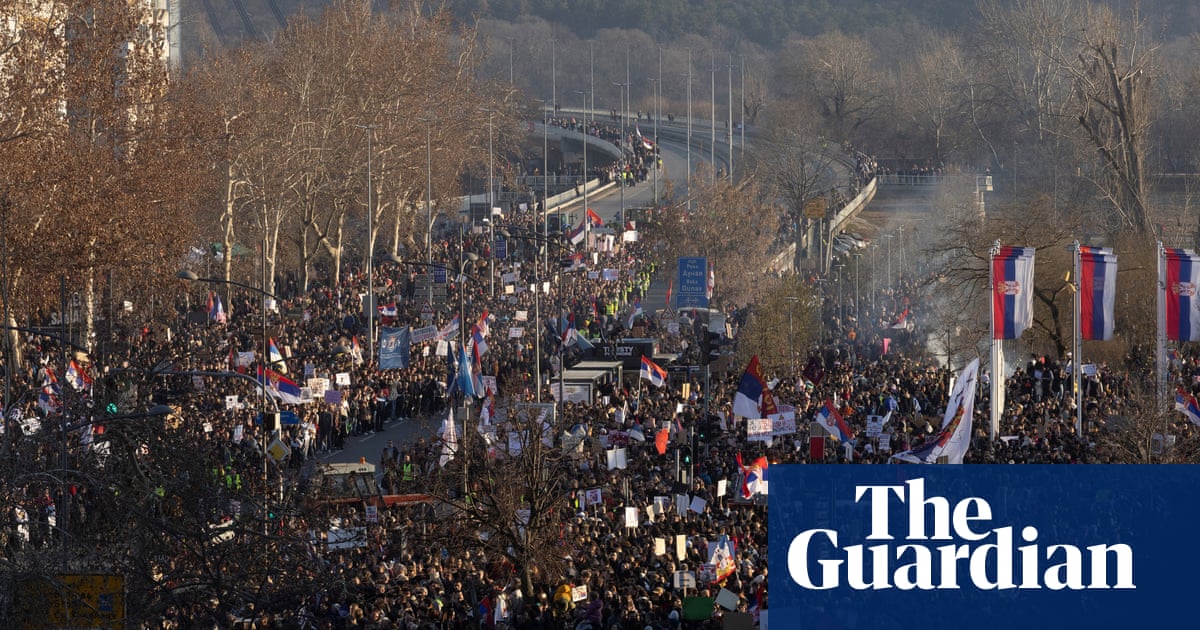

Three months to the day after a concrete canopy collapsed at the entrance of Novi Sad’s railway station, tens of thousands of protesters converged on the northern city, blockading its three bridges in commemoration of the 15 people killed in the accident. The tragedy has been blamed squarely on government ineptitude and graft.

“What we are seeing are the greatest street protests in the history of Serbia,” said Dejan Bagarić, a master’s student speaking from the city. “There’s never been anything like it, people are really animated because everybody has had enough of corruption and this government is very corrupt.”

Saturday’s outpouring of dissent – the culmination of sit-ins and protests that began in November – have focused on what demonstrators have described as the government’s striking unwillingness to accept any accountability for the tragedy. Reconstruction of the station was carried out in collaboration with a Chinese state consortium as part of a large infrastructure project that critics contend paid little, if any, attention to safety regulations.

“There was no transparency, no public tenders for the contract and then when the accident happened no desire for justice,” said Čedomir Stojković, a leading human rights lawyer who filed a criminal complaint that eventually spurred prosecutors to launch an inquiry. “Instead, the government did what it always does, it went ahead with a full-scale cover-up. There’s a lot of solidarity, a lot of empathy for the students, more and more people are coming out in support of them, professors, farmers, everyone.”

By last week the anti-government rallies had spread to more than 100 provincial towns and villages nationwide.

The scale of the protests had, said Stojković, proved “beyond any doubt” that the demonstrations were not only fuelled by disgust over corruption, an ill that has has come to be identified with everything that is wrong with the EU candidate nation, but were a way for citizens to vent their unhappiness with their nationalist president’s increasingly authoritarian rule.

For a generation raised on the internet, knowledge of the world beyond impoverished Serbia is readily available. Also unprecedented is the ability to rapidly arrange protests by circumventing state-controlled media – tens of thousands of striking students participated in a 24-hour blockade of a major intersection in Belgrade last week.

Vučić had faced similar protests last year following allegations of rigged elections, facilitated, opponents say, by a media landscape that remains one of the most censored in Europe. Unlike these demonstrations, however, it was opposition parties, themselves often discredited, who led the backlash.

“People want the government and Vučić to finally go,” said Stojković, who participated as a student in mass protests over 25 years ago against Slobodan Milošević, the late Yugoslav strongman whose policies triggered the region’s descent into bloodthirsty genocide. The protests paved the way to Milošević eventually being toppled in 2000.

“These students were children when Vučić became president eight years ago and they want democracy. It’s been building up … this is the moment just before the balloon is pricked by the needle. It has caught [the government] unaware.”

On Friday as hundreds of students reached Novi Sad on foot after a two-day, 80km trek from Belgrade, Vučić, addressing the protests, told the nation: “Our country is under attack, from abroad and from inside,” echoing earlier claims that the protesters were working for unspecified foreign powers to oust the government.

The ruling Serbian Progressive party has tried to defuse the situation by releasing classified documents into the railway station’s collapse and has even gone so far as to say it will meet all the students’ demands. This week, in what was seen as a first victory, Vučić’s close ally, prime minister Miloš Vučević, resigned but few believe the protests are about to fizzle out.

With youth unemployment at record levels and graduates forced in ever growing numbers to move abroad in search of work, there is a growing sense among young Serbs that there is little to lose.

To defy government crackdowns, the students have deliberately avoided being associated with a leadership of any sort ensuring that decisions are taken in concert in plenary sessions.

“We are not choosing violence and for now the government is not choosing violence either,” Bagarić said at the protests in Novi Sad.

As the protests swelled, Srđan Milivojević, who leads the opposition Democratic party, said it was clear Serbia’s young demonstrators were now dictating events.

“It’s irrelevant how the government reacts,” he said as he drove along the car-choked highway linking Belgrade with Novi Sad. “The students are dictating the tempo of the protests and they will continue to do so until Vučić falls.”

Article by:Source: Helena Smith