The enduring mystery about William Henry Gates III is this: how did a precocious and sometimes obnoxious kid evolve into a billionaire tech lord and then into an elder statesman and philanthropist? This book gives us only the first part of the story, tracing Gates’s evolution from birth in 1955 to the founding of Microsoft in 1975. For the next part of the story, we will just have to wait for the sequel.

In a way, the volume’s title describes it well. In the era before machine learning and AI, when computer programs were exclusively written by humans, the term “source code” meant something. It described computer programs that could be read – and understood, if you knew the programming language – enabling you to explain why the machine did what it did.

So what can we learn from inspecting Gates’s code? Broadly speaking, the message is that he was a very lucky lad. He was born in the right place at the right time to parents who gave him, he writes, “the precise blend of support and pressure I needed: they gave me room to grow emotionally, and they created opportunities for me to develop my social skills”. His account suggests, though, that it was an uphill battle at times. Bill Snr and Mary Gates discovered that they had a boy who was a strange blend of high IQ, arrogance, rebelliousness and insecurity.

“If I were growing up today,” he writes, “I probably would be diagnosed on the autism spectrum. My parents had no guideposts or textbooks to help them grasp why their son became so obsessed with certain projects, missed social cues, and could be rude or inappropriate without seeming to notice his effect on others.”

He was lucky. The Gateses were moderately affluent (his father was a prominent lawyer in Seattle) and they sent him to a remarkable private school – Lakeside – that was relaxed, liberal, supportive and tolerant. Which was good for a boy who was small for his age, with a reedy voice.

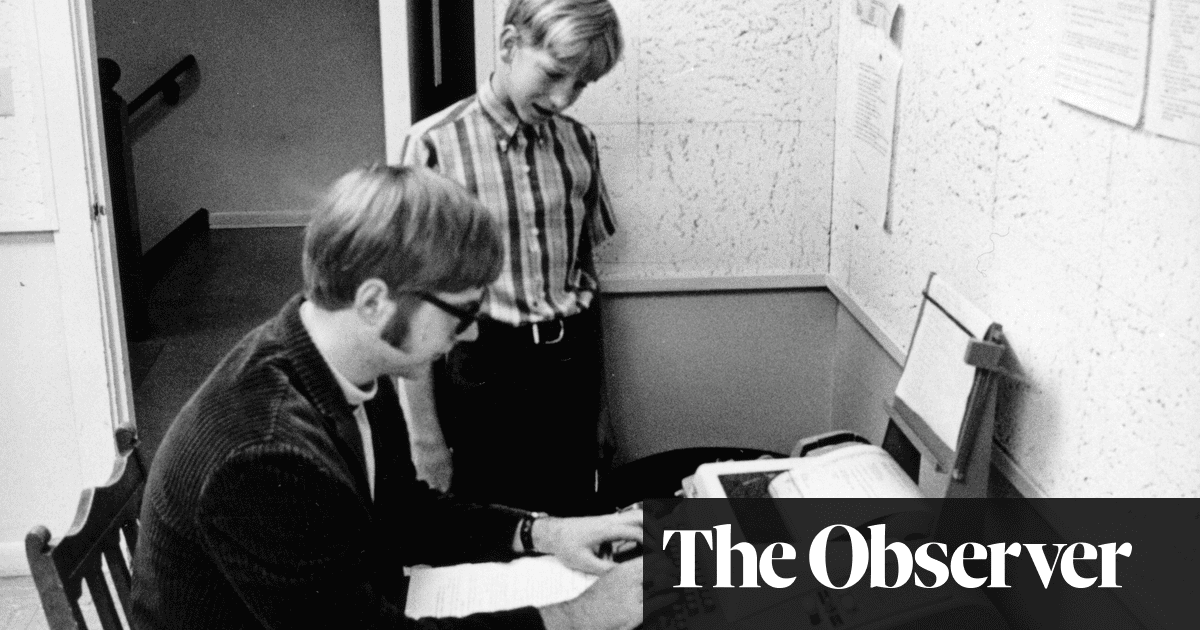

More significantly, perhaps, some of the parents had raised enough money to buy a Teletype terminal and a block of computer time on a General Electric time-shared computer for pupils’ use. This was extraordinary in the 1960s; it meant that Gates and some of his friends were writing software in their teens. He and a few others (including Paul Allen, with whom he later co-founded Microsoft) even started writing software for companies in the Seattle area. And when the school eventually went coeducational, Gates and his mates wrote the software for scheduling classes and activities in the expanded institution.

From Lakeside he went to Harvard in 1973, determined to sample everything that vast institution offered, while relying on his remarkable ability to cram ferociously before tedious assignments like exams. He inveigled his way into the university’s Aiken lab, which had just taken possession of an early minicomputer, a DEC PDP-10. But two years into this idyll, Allen turned up one day with the news that MITS, a two-bit firm in New Mexico, had just launched a microcomputer based on Intel’s 8080 processor chip.

This freaked them both out, because they had been pondering how to get into what they knew was going to be a huge industry and now this outfit in Albuquerque had scooped them with a crummy little machine. But the new device did not have any application software. So they set about writing – on the Harvard computer – an interpreter for the Basic programming language, using an ingenious software emulation of the MITS machine that Allen had written. This remarkable project was successful, but the university discovered that none of it had been authorised, and Gates was disciplined – much as Mark Zuckerberg was, many years later, for another illicit use of Harvard resources.

At this point, Gates dropped out and went, with Allen, to New Mexico, where they co-founded what was originally called Micro-Soft, and embarked on the path that led to great riches and industrial power. But that story has to wait for another volume, which will have to record how a powerful corporation became, for a long time, an institutional extension of its co-founder’s personality. And ran into antitrust litigation as a result.

after newsletter promotion

What’s striking about the present volume, though, is the reflectiveness of Gates’s account of his early development. He was clearly a difficult child to manage, especially as his mother had very clear ideas about how life should be organised. From an early age, young Bill rebelled against her rigorous regime. There were lots of fights and arguments. In the end, his parents sent him to a therapist, who turned out to be sympathetic and wise.

The biggest tragedy in his early life was the sudden death of his best friend (and fellow programmer), Kent Evans, in a mountaineering accident. “Kent’s dad greeted us and shook our hands,” he writes about going back to the family home after the funeral. “Kent’s mom was curled up on the sofa, sobbing. It was at that moment I understood that for all my grief, it would never run as deep as hers. He was my best friend, but he was her baby. At some level I knew that she and Mr Evans would be forever marooned in this loss. The stricken expressions on the faces of Kent’s kind, gentle parents that day have never left me.”

In a nice coda, he describes running into Evans’s father many years later, and they have a long conversation about what might have been. Both believe that if Evans had lived he would have been the third co-founder of Microsoft. Now, there’s a thought.

Article by:Source: John Naughton