FRIDAY, JANUARY 10

■ This evening the Moon shines in line with Jupiter and Aldebaran, as shown below. How exactly in line? That will depend on your time and location. Watch the straightness of the line change hour by hour! Every hour, the Moon moves by nearly its own diameter eastward against the stars.

SATURDAY, JANUARY 11

■ Now the Moon, two days from full, forms a triangle with Beta and fainter Zeta Tauri, the Bull’s horntip stars, as shown above.

SUNDAY, JANUARY 12

■ Mars is nearest to Earth tonight, appearing 14.6 arcseconds wide and magnitude –1.4. That’s as bright as Sirius, which sparkles whitely about four fists to Mars’s lower right in early evening, and directly below Mars when they’re highest around midnight or 1 a.m. Lesser Procyon shines roughly midway between them and a bit to the right.

Once Mars and Sirius are both high above differential atmospheric effects, compare their brightnesses. If you are getting on in years, Mars may appear to you distinctly brighter than Sirius. As we age our eye lenses yellow to some degree; this means that older people see the world through yellow filters. Your brain adjusts remarkably well for changes in a scene’s color balance, both long-term and short-term. But directly comparing the apparent brightness of a white and a yellow-orange light of equal brightness (in visual v magnitude) may reveal the situation.

This is one more reminder that our experience of the external world (i.e. the sum of its qualia), and the actual external world, are two very different things. In fact they are entirely different orders of being — right down to the bottom. Your experience of things exists only inside the few dark cubic inches of your skull, in a neural model of the outer world that your brain creates from the inputs of your senses. This is the only way that your self-awareness, your personhood, can understand and interact with the external physical world, because your sense of being a self is also a neural phenomenon. The outer world, which exists independently of human awareness, is vastly richer and more variegated than our limited senses perceive or than a brain-sized neural model could ever fully mimic. And internal world-models only evolved in ways that helped creatures survive, thrive, and reproduce. Anything else would be selected out as a distraction and a biologically expensive waste of neural processing power. 1

MONDAY, JANUARY 13

■ Full Moon (exactly full at 5:27 p.m. EST). The Moon rises on the east-northeast horizon about five minutes after sunset (for North America). How early in twilight can you see it? As it climbs and twilight deepens, how soon can you see orange Mars just 2° or less to the Moon’s lower left? That’s about the width of your thumb at arm’s length. And fainter Pollux and Castor above the Moon? The scene above indicates the view from 40° N, 90° W, near the middle of the population of the U.S. and Canada.

■ And the full Moon occults full Mars this evening for the contiguous U.S., much of southern and eastern Canada, and much of Mexico. Remember when the December 2022 full Moon occulted Mars at opposition? Here comes a repeat!

Bob King writes in the January Sky & Telescope, “During the December 2022 Mars occultation, I tried to keep sight of Mars right up to the lunar limb with just my eyes. I failed miserably, losing the planet in the full Moon’s glare nine minutes before it disappeared. However, it was clearly visible in binoculars right up to the occultation. Viewing with my telescope, what struck me most was the compelling color contrast between the Red Planet and the gray Moon.”

I too was watching that night, from near Boston a little south of photographer Walker, where the Moon made a very near miss — by ¼ of Mars’s apparent diameter. I used a 12.5-inch reflector at 300x and wrote in my observing log, “The dazzling curved limb of the Moon with its irregularities and lines of shadow contrasted with the perfect round ball of the orange planet. Almost science-fictiony!” — it reminded me of a scene from a Star Wars movie. “Mars’s surface brightness was not as bright as the Moon’s, but not as great a difference as I expected. The color contrast added to the clarity and beauty.”

Map and timetables for tonight’s event. The first two tables, with predictions for many cities, are long. The first table gives the times of the star’s disappearance behind the Moon’s limb; the second gives its reappearance out from behind the Moon’s other side. Scroll to be sure you’re using the correct table; watch for the new heading as you scroll down. The first two letters in each entry are the country abbreviation (CA is Canada, not California). The times are in UT (GMT) January 14th. UT is 5 hours ahead of Eastern Standard Time, 6 hours ahead of CST, 7 ahead of MST, and 8 ahead of PST.

For instance: Use the first table to see that for Chicago, Mars disappears behind the Moon’s edge at 8:07 p.m. CST, then reappears from behind the opposite edge at 9:16 p.m. CST. From New York the times are 9:21 and 10:37 p.m. EST. For cities on the West Coast the tables show Mars being covered when the Moon is still low and twilight is still under way (the Sun has a small enough negative altitude to be worth listing).

The limb of the Moon will take about 30 seconds or more to cross Mars’s disk. The closer you are to the edge of the occultation zone on the map, the longer it will take.

TUESDAY, JANUARY 14

■ After dinnertime, the enormous Andromeda-Pegasus complex runs from near the zenith down toward the western horizon. Just west of the zenith, spot Andromeda’s high foot: 2nd-magnitude Gamma Andromedae, slightly orange. Andromeda is standing on her head. About halfway down from the zenith to the west horizon is the Great Square of Pegasus, balancing on one corner. Andromeda’s head is its top corner.

From its bottom corner run the stars outlining Pegasus’s neck and head, ending at his nose: 2nd-magnitude Enif, due west. It too is slightly orange.

WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 15

■ Mars is at opposition tonight, its closest to being exactly opposite the Sun in our sky. The three-day offset from its closest approach to Earth on the 12th is due to the ellipticity of Mars’s orbit (which has an eccentricity 0.093) and to a lesser extent the ellipticity of Earth’s (e = 0.017).

■ At this coldest time of the year, Sirius rises in late twilight. Orion’s three-star Belt points down almost to its rising place.

Right after Sirius clears the horizon, it twinkles surprisingly slowly and deeply through the thick layers of low atmosphere. And if you’ve ever watched Sirius rise from an airplane window at cruising altitude, you may have been struck by its doubly deep and slow twinkling. This happens because you’re seeing Sirius through almost twice as much lower atmosphere. The light from the star skims near the Earth’s surface where a ground observer would be, then continues on through more of the lower atmosphere and up again to the airplane.

Sirius twinkles faster and more shallowly as it gains altitude. Its flashes of color also moderate, blending into shimmering whiteness as it climbs to shine through thinner air.

All stars show these effects, but the brilliance of Sirius makes them more salient.

THURSDAY, JANUARY 16

■ Zero-magnitude Capella high overhead, and zero-magnitude Rigel in Orion’s foot, have almost the same right ascension. This means they cross your sky’s meridian at almost exactly the same time: around 9 or 10 p.m. now, depending on how far east or west you live in your time zone. (Capella goes exactly through your zenith if you’re at latitude 46° north: near Portland, Montreal, Minneapolis, central France, Odesa, Kherson.) So whenever Capella passes its very highest, Rigel always marks true south over your landscape, and vice versa.

This winter, brighter Jupiter is a little to the right of the midpoint between them, trying to steal the show. They don’t seem to care.

FRIDAY, JANUARY 17

■ Here it is the coldest very bottom of the year on average. But the Summer Star, Vega, is still barely hanging in! Look for it twinkling over the northwest horizon during and shortly after nightfall. The farther north you are the higher it will be. If you’re as far south as Florida it’s already gone.

■ Venus and Saturn, in the southwest during and after dusk, now appear just 2¼° apart as shown above. That’s about the width of your thumb at arm’s length. Saturn is left of Venus. How early can you first see it?

SATURDAY, JANUARY 18

■ This evening Venus and fainter Saturn are 2.2° apart, just a trace closer together than they appeared yesterday. And, Saturn is now lower left of Venus. Today is their actual conjunction date (i.e. in ecliptic longitude). From now on Saturn will move away farther below Venus.

■ On the other side of the sky in the southeast, Sirius twinkles brightly after dinnertime below Orion. Around 8 or 9 p.m., depending on your location, Sirius shines precisely below fiery Betelgeuse in Orion’s shoulder. How accurately can you time this event for your location, perhaps by judging against the vertical edge of a building? Of the two, Sirius leads early in the evening; Betelgeuse leads later.

SUNDAY, JANUARY 19

■ Right after dark, face east and look very high. The bright star there is Capella, the Goat Star. To the right of it, by a couple of finger-widths at arm’s length, is a small, narrow triangle of 3rd- and 4th-magnitude stars known as “The Kids.” Though they’re not exactly eye-grabbing, they form a never-forgotten asterism with Capella.

This Week’s Planet Roundup

Mercury, magnitude –0.4, is sinking away into the glow of sunrise. Early in the week, look for it low in the southeast about 40 or 50 minutes before sunup. Binoculars may help. (Don’t confuse Mercury with Antares much higher, at least two fists to Mercury’s upper right.)

Venus, magnitude –4.6 in Aquarius, shines very high and bright as the “Evening Star” in the southwest during twilight, and lower in the west-southwest as evening grows late. It doesn’t set until about 2½ hours after dark.

As darkness deepens you’ll spot Saturn, much fainter, upper left or left of Venus and closing in on it day by day. See Saturn below.

Get your telescope on Venus early in twilight. This week it appears very nearly half-lit, at or just past dichotomy. Venus is enlarging week by week as it swings toward us, while waning in phase as it swings closer to our line of sight to the Sun. It has already enlarged to 25 or 26 arcseconds from pole to pole. It’ll be twice that size by the time it turns to a thin crescent plunging down near winter’s end.

Mars is at opposition this week, glaring at magnitude –1.4 near the Cancer-Gemini border below Castor and Pollux. It comes into view as a steady orange spark low in the east-northeast in twilight. Watch Mars shift position night by night to line up with Castor and Pollux on January 16th and 17th.

Mars shows best in a telescope from late evening through the middle of the night, when it’s very high toward the southeast or south. It is now 14.5 arcseconds in apparent diameter and will touch 14.6 when closest to Earth on January 12th. Opposition comes three days later on the 15th. But this is a relatively distant opposition for Mars. It’s near the aphelion of its fairly elliptical orbit, the orbit’s farthest point from the Sun.

A map of the major Martian surface features is in the January Sky & Telescope, page 48, in Bob King’s article “Mars is in Fine Form.” To find which side of Mars (i.e. which part of the map) will be facing you at the time you’ll observe, use our Mars Profiler tool.

See also Bob’s Mars Extravaganza — Occultation and Opposition Rolled into One! including surface-feature map.

South is up. Thaumasia and Solis Lacus are at top. Tithonius Lacus is the largest dark area in the big dark prong just below Solis Lacus. The North Polar Cap is rimmed with dark. Mars was 14.0 arcsec wide.

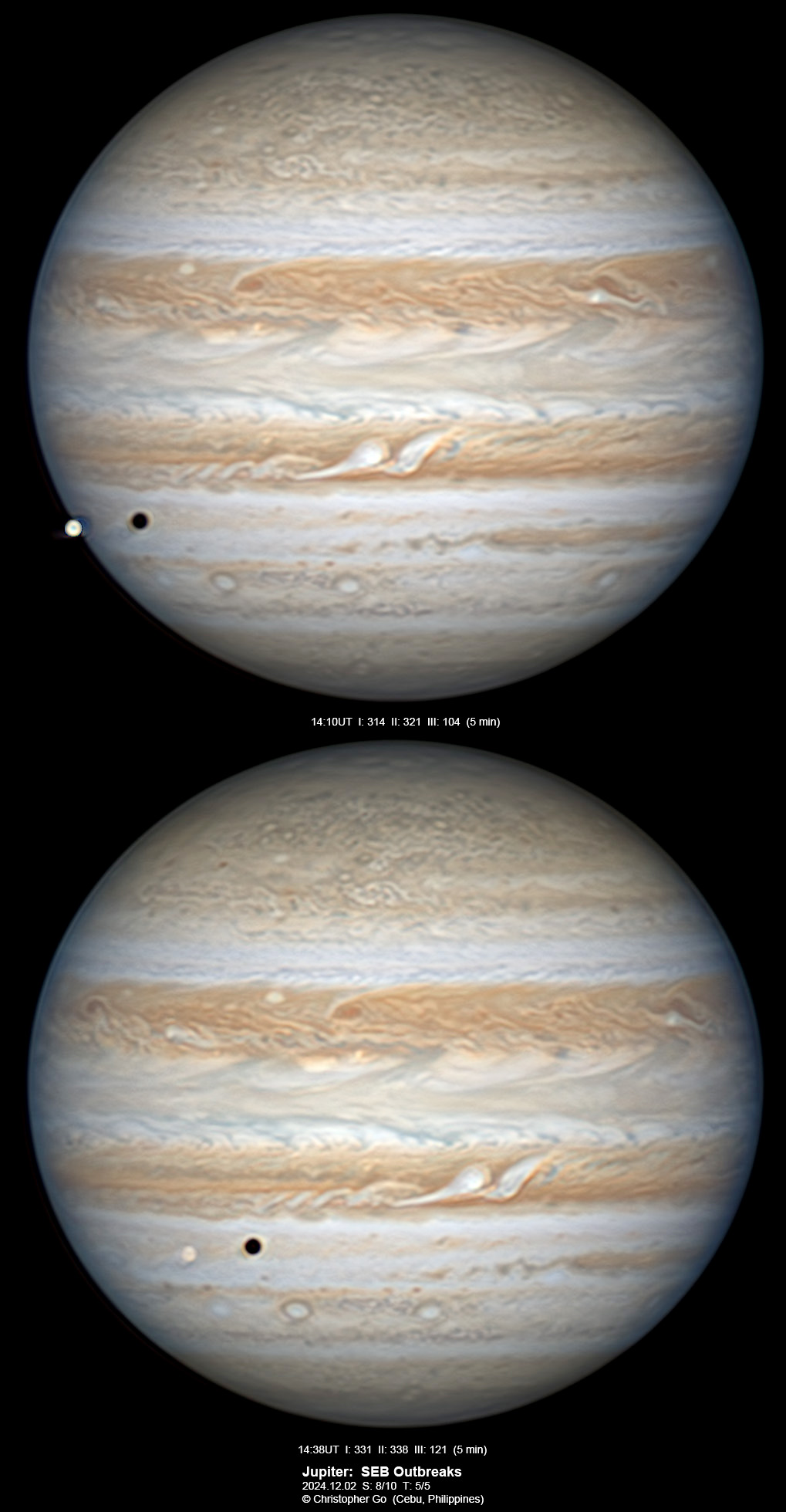

Jupiter, more than a month past its own opposition, shines at a bright magnitude –2.7 in Taurus. It dominates the high east to south during evening, with fainter Aldebaran (orange), fainter Beta Tauri ( bluish white), and the Pleiades nearby. Jupiter is still a good 45 arcseconds wide.

Saturn, magnitude +1.1 in Aquarius, glows in the southwest after dark, upper left of Venus and closing in on it fast. Saturn is 7° from Venus on January 10th. They’ll pass each other by 2.2° at conjunction on January 18th.

Uranus (magnitude 5.7, at the Taurus-Aries border) is very high during evening, 18° west of Jupiter. You’ll need a good finder chart to tell it from the similar-looking surrounding stars. See last November’s Sky & Telescope, page 49.

Neptune (tougher at magnitude 7.9, under the Circlet of Pisces) is fairly high in the southwest right after dark, upper left of Saturn and Venus. Again you’ll need a sufficient finder chart.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world’s mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions and graphics that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America.

Eastern Standard Time (EST) is Universal Time minus 5 hours. UT is also known as UTC, GMT, or Z time.

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They’re the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For a more detailed constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you’ll need a much more detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas, in either the original or Jumbo Edition. Both show all 30,000 stars to magnitude 7.6, and 1,500 deep-sky targets — star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies — to search out among them.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5; nearly three times as many, as well as many more deep-sky objects. It’s currently out of print, but maybe you can find one used.

The next up, once you know your way around well, are the even larger Interstellarum atlas (201,000+ stars to magnitude 9.5, and 14,000 deep-sky objects selected to be detectable by eye in large amateur telescopes), andUranometria 2000.0 (332,000 stars to mag 9.75, and 10,300 deep-sky objects). And read How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope. It applies just as much to charts on your phone or tablet as to charts on paper.

You’ll also want a good deep-sky guidebook. A beloved old classic is the three-volume Burnham’s Celestial Handbook. An impressive more modern one is the big Night Sky Observer’s Guide set (2+ volumes) by Kepple and Sanner. The pinnacle for total astro-geeks is the new Annals of the Deep Sky series, currently at 11 volumes as it works its way forward through the constellations alphabetically. So far it’s up to H.

Can computerized telescopes replace charts? Not for beginners I don’t think, and not for scopes on mounts and tripods that are less than top-quality mechanically. Unless, that is, you prefer spending your time getting finicky technology to work rather than learning how to explore the sky. As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer’s Guide, “A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand and a curious mind.” Without these, “the sky never becomes a friendly place.”

If you do get a computerized scope, make sure that its drives can be disengaged so you can swing it around and point it readily by hand when you want to, rather than only slowly by the electric motors (which eat batteries).

However, finding faint telescopic objects the old-fashioned way with charts isn’t simple either. Do learn the essential tricks at How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope.

![]() Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

earbuds in place, listen to Kelly Beatty’s monthly

podcast tour of the naked-eye heavens above. It’s free.

“The dangers of not thinking clearly are much greater now than ever before. It’s not that there’s something new in our way of thinking, it’s that credulous and confused thinking can be much more lethal in ways it was never before.”

— Carl Sagan, 1996

“Facts are stubborn things.”

— John Adams, 1770

1. Recommended reading:

Being You, Anil Seth (Dutton)

Our Mathematical Universe, Max Tegmark (Vintage)

Article by:Source – Alan MacRobert